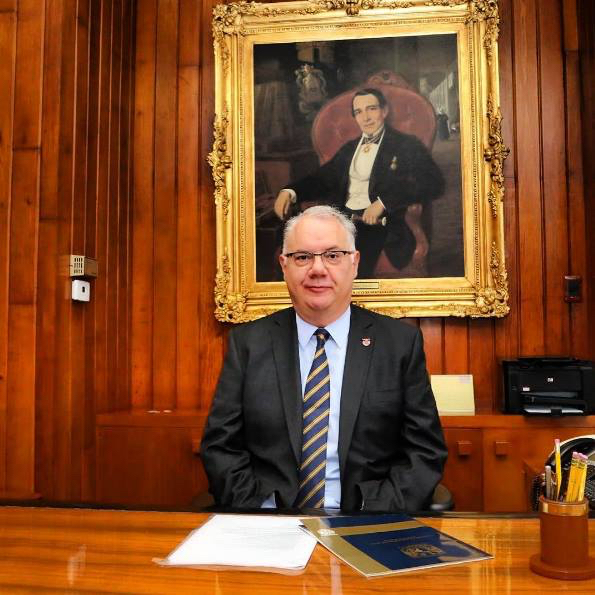

Germán Fajardo Dolci, director of the School of Medicine at Mexico’s UNAM (The National Autonomous University of Mexico), one of the most important in Latin America, talks about innovative strategies to improve students’ undergraduate competencies, including the use of digital tools for decision-making and publishing research.

by Matias Loewy

Dr. Germán Fajardo Dolci is an ear, nose and throat specialist, has a Master’s Degree in Senior Management and is the Director of the Faculty of Medicine of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), “the oldest and most important in the country because of its size, number of students and careers and the number of graduates over the centuries,” he says. With origins dating back to the mid-16th century, the university today offers a degree in surgical medicine, which 94% of its 8,000 undergraduate students take; alongside degree programs in Neurosciences, Forensic Science, Physiotherapy, Basic Biomedical Research and Human Nutrition, as well as a Combined Studies Plan in Medicine (PECEM), which combines an undergraduate degree with a doctorate in Medicine over a period of up to nine years. In an interview with E-Health Reporter Latin America, Fajardo, who began a second term in office in 2020 (until 2024), discusses the challenges, progress, tools and projects he is undertaking to improve the skills of future physicians.

. How prepared have medical graduates been to enter the competitive job market?

Graduates have all the possibilities, as big as the alphabet: I say it goes from A for anthropology to Z for zoology. That is the spectrum. Of course, we have the doctor who wants to see patients, who wants to focus on general medicine or a specialty. But to do a specialty, they have to pass the National Exam for Medical Residency Applicants (ENARM), something achieved by a third of the applicants. While being a specialist is the most popular, there are other areas of medicine, which are not necessarily the traditional clinical ones, but make a big impact in our day to day lives. For example, master’s and doctoral degrees in public health, administration, epidemiology, and so on. Our graduates are engaged in a wide variety of activities and most of them are very successful.

. In what ways have you tried to modify curriculum so that professionals are better prepared to meet the challenges of the future?

The current study plan is 10 years old. Due to regulations the first graduates of the plan have to pass in order to be able to evaluate it. But we are working on this proposal for a new plan, so that it will be much more dynamic. We are looking for the new plan to be extremely flexible and to allow us to incorporate all of the changes that will come with the future needs. It seems like healthcare is moving at one speed and medical schools are moving at a slower one. To make up for this we have been able to promote electives and ongoing seminars, such as a very successful one on digital health in conjunction with the Slim Foundation. That covers topics that were not included in the 2010 plan, such as the so-called “omics” (such as genomics and proteomics), Internet of Things, 3D printing, nanorobots etc… we are trying to ensure our students know what is happening and amass more knowledge than those areas that are of interest to them.

. Another advance in the modernization of the medical curriculum is a greater focus on research. What has been the motivation for placing emphasis on this area?

Mexico (like Latin America in general) is more a consumer than a generator of knowledge. Most of what we read comes from abroad. Undoubtedly, we need to strengthen that area. On the research side, we have the PECEM program and the doctorate, but we also have a program called AFINES (Support and Promotion of Student Research), to which 20% of the students per year who are interested in research join a laboratory, a hospital or university research center. Another tool we use is the BMJ’s Research to Publication program, which we have found extremely useful.

. What are you hoping to achieve?

What we want is that, through this type of program, students not only become familiar with research, but that they can write a better publication. We have many limitations: we don’t necessarily know all the steps; the difference in language also limits our technical writing. Programs like Research to Publication help the teacher and the student to not only acquire more knowledge and apply it, but also that the research can have more dissemination and a broader impact and reach. We have it for undergraduates, and it also helps residents publish an article (a requirement for their training) in a major journal, with an impact factor, so that what they produce is read and helps other colleagues advance knowledge and improve patient care. Of course, having such knowledge and skills also helps to discern what to read and what not to read, whether a published study’s methodology, sample size or comparison with the reference standard is appropriate. This is also essential before embarking on one’s own research project.

. Clinical simulation as an educational strategy has been promoted for several years. Would you compare it to something like flight simulators to prepare future doctors before they “take off”?

Of course. The early contact of students with patients is essential, not only for the acquisition of technical skills, but also transversal skills, those that have to do with ethics or professionalism and the way they interact with the family and choose treatments. It is easy to learn by watching doctors; how he treats and explains things to the patient, how he transmits the therapeutic or educational proposals, and so on. But you also develop these skills through simulation. We have two simulation centers, one for undergraduate and another for postgraduate students. What we want is that similar to flight training, before doing a procedure, diagnosis or indication, the student or graduate has to go try it in the simulator until he/she acquires the skills, or reinforces those already learned (because doing it once a year is not enough to ensure patient safety). So, there are simulations with the Gesell camera, with cameras and microphones, where the student interrogates the patient in a technical and human way; and also with mannequins, where computers are used to observe the response in terms of vital signs of certain interventions, such as the administration of a drug.

. Regarding the incorporation of digital tools for clinical decision making from the undergraduate level, what has been UNAM’s experience with BMJ Best Practice?

There are several tools for that purpose on the market and BMJ Best Practice is one of them. It has worked very well for us. For the doctor who is with a patient and asks any clinical, diagnostic, treatment, prognostic question, suddenly we don’t have the time to look for all the information there is on a certain topic. And precisely this type of tool helps to synthesize the information. If you ask the right question, it helps to have the right answers and to be able to present the patient with the best options for him and his environment.

. How do you project that digital transformation will impact the physician’s practice of the future?

Very much so. It’s not a matter of opinion, we’re seeing it. This pandemic has meant that many tools that have been available to us but that we were a bit reluctant to use, such as telemedicine, are here to stay. Patients for various reasons have “nosophobia,” which is the fear of going to the hospital. The patient wanted to go and talk to the doctor, and today those patients can do so through these channels. There are also smart devices that allow the doctor to monitor a patients glucose level when they wake up, what the blood pressure or different vital signs are from afar. And we already have personalized medicine, which today may seem more expensive, but in the end, it will be cheaper, because knowing which drug is right for a person or what their risk is of developing a disease allows us to specifically target prevention or treatment.

. Still seeing patients?

I have stopped seeing patients in recent years, because of the time this responsibility takes me. But it is difficult for a doctor with a true vocation of service to escape from the three “legs”: medical care, education, and research. I would like every student who passes through the faculty of medicine to be able to achieve his or her particular dream, whatever his or her area of practice. We can’t all be as famous as Dr. Ignacio Chavez (1897-1979), but we can be better every day. The only answer to that is dedication, commitment, hard work and the vocation to serve others.